|

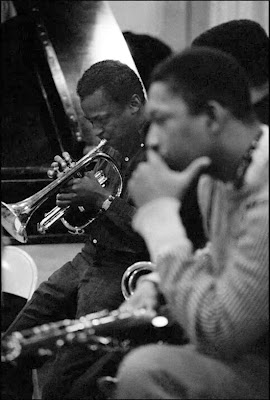

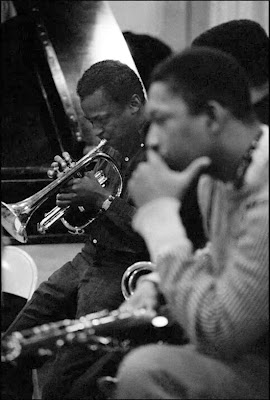

Coltrane with Miles

|

|

Miles, Cannonball Adderley, and Coltrane

|

|

Coltrane House in Philadelphia

|

|

Dix Hills home, Long Island

|

|

John Coltrane with Alice

|

|

Coltrane with McCoy Tyner

|

CHASING TRANE: THE

JOHN COLTRANE DOCUMENTARY B+ USA

(99 mi) 2016 d: John Scheinfeld

An essential portrait in the life of a jazz giant and a companion

piece to Stanley Nelson’s Miles

Davis: Birth of the Cool (2020), as both Miles and Coltrane’s lives were

forever altered by experiencing the genius of Charlie Parker in concert at a

young age, as he was capable of doing things on his alto saxophone that no one

else had ever done, literally blowing the minds of these developing young

musicians. Miles and Coltrane may be the

two most iconic figures in American jazz, and they collaborated at the height

of their respective careers, with Coltrane initially working with Miles in

1955, believing at the time he had reached a zenith in his career, but he

followed too closely in the footsteps of Parker, prey to the seductive pimps

and drug pushers that hung around jazz clubs in those days, developing a heroin

habit, even at the expense of his career, where he and saxophonist Jimmy Heath

were caught getting high between sets, both immediately fired by Davis, who

didn’t allow drugs to interfere with the business of making music. Coming early on in the film, it provides

something of a jolt, as immediately he’s canned and out on his ass before the

film really had a chance to get started.

Down in the doldrums, he goes cold turkey, something requiring great

fortitude, going through withdrawals on his own, with his stepdaughter Antonia

Andrews recalling he was vomiting all night and sick with fever, but each

successive day he was a little bit better.

Flashing back to his boyhood in North Carolina, both of his grandparents

were preachers, so he grew up immersed in the church, where spiritual salvation

was at the fiber of his being, fixating on music as a lifeline in the Jim Crow

South, as his mother sang and played piano, while his father played clarinet

and violin. According to Dr. Cornel

West, who taught classes on Coltrane at Princeton and who himself is the

grandson of a Baptist minister, explaining how blacks came out of the brutal

conditions of slavery, “We gonna share and spread some soothing sweetness

against the backdrop of a dark catastrophe.

That’s black music,” claiming further, “Black music was the response to

being traumatized.” Experiencing some

dark times, at age 12 he lost his father, uncle, and two grandparents in the

space of just two years. Out of work and

needing a source of income, his mother moved to Philadelphia and made enough

money to afford music lessons for her son, buying him his first saxophone,

switching from the clarinet to the saxophone.

Coltrane was in the Navy stationed at Pearl Harbor after the war,

recording with other enlisted men in an all-white swing band playing jazz

standards and be-bop tunes, returning to Philadelphia afterwards to study jazz

theory on the G.I. Bill. According to

Wynton Marsalis, listening to those early Navy recordings offer no indication

whatsoever of the astounding talent he would become. Made with the support of the John Coltrane

Estate, utilizing astonishing, never-before-seen Coltrane family home movies,

footage of John Coltrane in the studio with Monk, Miles Davis and others, along

with hundreds of never-before-seen photographs and rare television appearances from

around the world, incisive commentary is provided from musicians that worked

with him, like childhood friend Benny Golson, Jimmy Heath, Wayne Shorter, and

the always real Sonny Rollins, but also those who have been inspired by his indomitable

artistry, including Wynton Marsalis, Carlos Santana, Doors drummer John

Densmore, and Common, along with a surprisingly eloquent President Bill

Clinton, who famously plays the saxophone, with more commentary from Coltrane’s

own children, two of his biographers, Ben Ratliff and Lewis Porter, and jazz

scholar Ashley Kahn. What separates

Coltrane from everyone else is that after he gets clean from drugs and alcohol,

he then goes on a creative, artistic and spiritual quest the likes of which we

have perhaps never seen over a 10-year period by any artist in any medium,

becoming one of the seminal figures of jazz.

It might recall the legendary bluesman Robert Johnson whose life and

death remain shrouded in mystery, growing up in the Mississippi Delta during

the Great Depression, whose musical skills, according to bluesman Son House,

were less than stellar. But after going

down to the proverbial crossroads and traveling across the Delta for two years

(making a mythological deal with the devil), he returned a bona fide genius of

his craft, summoning skills seemingly from out of nowhere, Robert

Johnson: The Life And Legacy Of The Blues Giant, doing an infamous

recording session over the course of five days, producing just 29 songs, but

nearly all of them have become classic standards in the blues canon, forever known

as a master of the blues. Entirely

scored with the music of John Coltrane, as access was granted from the entire

catalogue, music becomes the major focus of the film, serving as an unspoken

narration heard throughout, as he never speaks onscreen, instead Denzel Washington

reads from his own interviews and liner notes published between 1957 and 1967. One major drawback is the persistent use of paintings

from the colorfully animated artwork of Rudy Gutierrez in Gary Golio’s children’s

book Spirit Seeker – John Coltrane’s

Musical Journey. Rather than enhance

the emotional barometer of the artist, this feels somehow indulgent, not so

much about Coltrane as another man’s artistic vision.

In the late 40’s and early 50’s Coltrane worked with Dizzy

Gillespie, but it wasn’t until he worked with Miles Davis that his career took

off, known as the “First Great Quintet,” which disbanded after Coltrane’s

heroin addiction, with Davis aggravated by his unreliability, but once he

experienced what he described as “a spiritual awakening,” getting completely

off drugs and alcohol, where he’s more clear-headed and sharper mentally, his

music changed. Spending time under the

tutelage of Thelonious Monk, with his unique sense of time and composition, refining

his skills, learning about harmonic progression, he worked alongside Monk at

the Five Spot Café in a 6-month residency in the latter half of 1957 before

rejoining Miles Davis in 1958, recreating a small band that simply changed the

course of jazz, performing in a quintet/sextet that primarily spotlighted the

introverted Coltrane, who was solitary yet driven, serving as a catalyst,

providing a greater depth of expression that Davis was seeking. Miles saw in Coltrane an intelligent, deeply

probing and creatively inventive artist mirroring the professionalism in how he

viewed himself, often lacking in fellow musicians. What sustained and influenced Miles in his

relationship with Coltrane was not only his sound and the innovation of his

improvisations, but the quality of their musical dialogue together, exploring various

relationships of intervals in chord construction and melodic variation,

reacting in conversations to one another onstage, where Miles was lyrical and

succinct, while Coltrane was more rhapsodic.

Offstage they had diametrically opposite personalities, as Coltrane was

quiet, pensive, and self-critical to a fault, practicing obsessively, while

Davis was arrogant, cocksure, and demanding, surrounded by the company of

friends, often venturing into the public eye.

But once they took the stage they reversed roles, as Coltrane was more

freely uninhibited in his constant exploration, while Davis became the more

sensitive introvert, often muted and hushed, exuding vulnerability. Miles quickly realized that Coltrane was not

just a great sideman, but the perfect counterpoint to his own subdued

trumpet. According to Miles, “After we

started playing together for a while, I knew that this guy was a bad

motherfucker who was just the voice I needed on tenor to set off my voice.” Their contrasting approach was even more

pronounced during impromptu performances, as Coltrane was obsessing over

harmonic variation and would take even more extended time for his

improvisations, as his solos grew longer and longer, rare for Davis to allow, but

he couldn’t silence this magical voice.

When they stepped into a recording studio, they first recorded Milestones - Miles Davis -

(Full Album) (48:00), legendary in its own right, and then M I L E S D A V I S -

Kind Of Blue - Full Album (1:18:05), the most successful jazz album in

history. In 2009, the U.S. House of

Representatives passed a resolution that honored it as a national treasure,

sumptuous and vital music that’s alternately exhilarating and emotive,

rhythmically dynamic and smoothly flowing, complex and easy on the ear. It’s music that defies classification. What had been great jazz from the earlier

1955-57 Davis quintet, now broke through to a category of timelessness, finally

fulfilling the promise of their collaborative magic. But Coltrane’s self-assurance only grew in

stature, literally outgrowing the group, feeling straightjacketed by the small

combo format, needing more time to explore on his own, heading his own group

and releasing his own album John Coltrane

- Giant Steps (2020 Remaster) [Full Album] (37:32) just a few weeks

afterwards, writing all of the compositions himself, including the hauntingly

beautiful composition named after his wife, Naima - YouTube (4:25),

allegedly Coltrane’s favorite. It was a

declaration of creative independence, acknowledging Coltrane’s arrival as a

fully matured, triple threat, a soloist, bandleader and composer. His musical vision was leading him in a

direction away from Miles, who sensed Coltrane drifting away. While there’s nary a contrary word spoken

against him in the entire film, which, in itself, is remarkable, Coltrane was a

man of few words, who let his music speak for him. Jazz critic Ira Gitler coined the term “sheets

of sound” to describe his style, as he strung together arpeggios so dense that

his saxophone seemed to play multiple notes at once.

A creative restlessness continually propelled John Coltrane,

becoming fanatical about practicing and developing his craft, practicing “25

hours a day” according to Jimmy Heath, who recalled an incident in a San

Francisco hotel after a complaint was issued, so Coltrane took the horn out of

his mouth and silently practiced fingering for a full hour. Before Coltrane, jazz was urban music,

expressing a mournful, existential sound of the city, but Coltrane took that

sound and honed it down to its transcendent core, becoming an affirming and

ecstatic sound of faith. First he moved

to the soprano sax to produce variations on a mainstream show tune from The Sound of Music that became an

extremely popular crossover hit, My Favorite Things

- John Coltrane [FULL VERSION] HQ (13:46), featuring Jimmy Garrison on bass,

the free-flowing style of Elvin Jones on drums, and the remarkably inventive McCoy

Tyner on piano, whose foundational layers of chordal support were

complimentary, yet revolutionary in their own right. Coltrane divorced his first wife, where heated

acrimony in the household was simply never previously seen, as both were

inwardly reserved, but he met pianist Alice McLeod at the club Birdland, got

married and raised a family with three children. By all indications both were gentle spirits,

quiet and inwardly spiritual, yet home movie videos reveal these were the

happiest years of his life, relaxed and content with his new role as a father, seen

smoking his pipe in the back yard, playing with a dog and the couple’s

children, while continuing to explore the outer and inner realms of his

spiritual dimensions, disappearing into an attic above the garage in their home

on Dix Hills, Long Island, eating only sporadically while remaining

sequestered, working on a new musical composition, but when he was finally

finished, sheet music in hand, according to his wife, “it felt like Moses

coming down from the mountain.” Shaped

by his inner faith, it would be his opus jazz record, a four-part suite called A Love Supreme, John Coltrane - A

Love Supreme [Full Album] (1965) YouTube (32:48), which was released in

1965, his pinnacle studio outing and one of the most acclaimed jazz records

ever, surpassed only by Kind of Blue, Top 25 Jazz

Albums of All Time, widely recognized as a work of deep spirituality with

an underlying religious subtext, a journey into the realms of religious

exaltation, a hymn-like anthem of love offering peace and supreme praise to

God. Carlos Santana insists that he

plays the music whenever entering hotel rooms, cleansing the surroundings of

any lingering evil spirits, keeping the bad vibes away. Among the more compelling aspects of the film

is its drive to an emotionally poignant finale, where one of the film’s most

powerful sequences comes with the stark black-and-white footage of protesters

being attacked with water hoses and police dogs in the wake of the tragic

Birmingham bombing as Coltrane’s haunting

Alabama plays, John Coltrane - Alabama YouTube

(5:09). He wrote the song in response to

the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing in Birmingham, Alabama, 16th Street Baptist

Church Bombing (1963) - National Park ..., a moving lament written in

memory of four little girls who were murdered by a Ku Klux Klan bombing, where

the mournful melody was inspired by the spoken cadence of Rev. Martin Luther

King at the eulogy, as Elvin Jones’s drumming rises from a whisper to a

pounding rage. When Dr. Cornel West

speaks of the work, “Martin Luther King Jr. and John Coltrane, hand in hand,

represent the best of the human spirit.” Coltrane’s group grew more avant garde, free

from all constraints and barriers, where the music was pure improvisation, throwing

themselves into abstract world music and the free jazz movement where solos

could last for more than an hour, with many in the audience walking out, as

Coltrane was going further out there in the cosmos than most listeners wanted

to go. According to John Densmore, “He

had the right to go out as far as he wanted,” while saxophonist Wayne Shorter

claimed Coltrane was preoccupied with the “seeking of universal truth.” Coltrane’s last tour was across Japan, where

he was embraced as a national hero. In

Nagasaki he asked to be taken to the Nagasaki Peace Park Memorial constructed

on the site where the atomic bomb was dropped in WWII, a sacred place to the

Japanese people, where he stood for some time meditating on the ghastly

experience. The centerpiece of the music

played that night was entitled Peace On

Earth, Peace On Earth

(Live At Shinjuku Kosei Nenkin Hall, Tokyo ... YouTube (25:01), a transcendent

work demonstrating not just a deep compassion for the country and its people,

but the suffering they endured after the atomic bombing. Introducing Coltrane that night was Yasuhiro

“Fuji” Fujioka, who has authored five books on Coltrane, and may be the #1

collector of Coltrane memorabilia in the world, building a shrine called The

Coltrane House in Osaka, コルトレーン・ハウス - livedoor, filled with

every record and all the memorabilia he could attain. His obsession with Coltrane started in high

school when he heard him on the radio, feeling it was an utter revelation, a

feeling that never left him. During the

end of the tour Coltrane complained of side pain and died suddenly at the young

age of 40 from liver cancer, happening very quickly, taking the world by

surprise. Coltrane left behind a

catalogue of musical recordings that include all the various phases he went

through in his creative development, with President Clinton indicating “He kind

of did everything Picasso did, in about 50 years less time,” while his wife Alice

Coltrane observed, “He always explored higher vistas knowing that there is

always something higher, something greater.”