|

| Louis Armstrong and his All-Stars |

|

| Patrice Lumumba |

|

| Max Roach |

|

| Andrée Blouin |

|

| Malcolm X |

|

| CIA director Allen Dulles with his everpresent pipe |

|

| Director Johan Grimonprez |

SOUNDTRACK TO A COUP D’ÉTAT A- Belgium France Netherlands (150 mi) 2024 d: Johan Grimonprez

History is the lie commonly agreed upon. —Voltaire

A stark assessment of how little we actually know about modern day history, where everything is cloaked in secrecy, as truth is a liability, telling one tale for public consumption while undermining that exact same position behind-the-scenes. Nothing new was shot for this film, as it’s all drawn from existing archival material, a truly radical, formally inventive effort, as the amount of research involved here is truly extraordinary, where the entire film consists of footage not shown when the events were happening, providing a glimpse behind the headlines of what the media was not telling you. Meticulously examining the 1961 assassination of Congo’s newly elected leader, Patrice Lumumba, where not much was known or written at the time, the film documents each and every source, looking behind the curtain at what really happened, creating a chilling portrait of the cruel manipulation of international affairs, where it’s all about the art of deception. Using American jazz as a connecting thread, including live performance footage, with improvisational music fueling a free form, avant garde, cinematic collage approach, this is something we haven’t really seen before, yet the scholarship in breaking down the various political smokescreens is impressive, using eyewitness accounts, official government memos, recorded United Nations debates, testimonies from mercenaries, CIA operatives, British intelligence, and speeches from Lumumba himself, along with published memoirs by Congolese activists and writers. The compelling subject matter is dense and often difficult to watch, juxtaposed against various jazz compositions that act as an underlying narrative, from Abbey Lincoln’s haunting rendition of Max Roach's Freedom Now Suite YouTube (9:08), a Civil Rights anthem, perhaps the best-known jazz work with explicitly political content, to the deeply soulful Nina Simone - Wild Is The Wind (Live In New York 1964) YouTube (7:00), or her jazzy rendition of a Bob Dylan anthem, The Ballad of Hollis Brown - Nina Simone 1965 YouTube (6:10), which starts and ends the film, to a Congolese song of liberation by Joseph Kabasele, aka Le Grand Kallé, "Indépendance Cha-cha" - Congolese Independence Song YouTube (3:05), where the film is full of contradictions and bumps along the road, with no talking heads or voiceovers, featuring teeny, tiny, academic footnotes onscreen that are hard to read, yet essential for any continuing dialogue which this film hopes to inspire, while the film itself is also two and a half hours long. Ostensibly a dissection of what was happening behind the scenes that led to the overthrow of Patrice Lumumba, the first democratically elected Prime Minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, whose government was overthrown in a US-backed military coup, as he was kidnapped, beaten bloody, and tortured by his captors before facing a firing squad, pouring sulfuric acid on his body to prevent identification, saving only his gold teeth as war trophies, where the announcement of his death was withheld for over a month. A rising star in Africa who essentially advocated a philosophy of Africa for Africans, aligned with Kwame Nkrumah in Ghana and Gamal Abdel Nasser in Egypt, beliefs that coincided with Malcolm X and many black jazz artists, as American black nationalist solidarity aligned with African liberation, Lumumba broke the yoke of colonialism while espousing freedom and democracy, beliefs that would normally be aligned with the West, sharing the same democratic principles, coming from hundreds of years of enslavement and colonialism, where the immediate outlook was bright, finally having their own country’s interests first and foremost. But Lumumba posed a threat to the West precisely for those principles, as the West wasn’t ready to break the link of readily available resources coming from minerals that had been plundered from the African continent for centuries, which includes uranium, as the Congo mines were the main source of uranium used during the Manhattan Project to develop atom bombs and harness nuclear energy, a significant factor during the Cold War, where it’s no coincidence that this was happening at the height of the nuclear arms race. The film addresses a diffuse mixture of base racism, colonial arrogance, and economic greed, less with agitational intent than as an enlightened treatise on injustice that remains just as relevant today. The foremost film on colonialism is Gillo Pontecorvo’s The Battle of Algiers (1965), which exposed France’s unwillingness to stop its colonial occupation of Algeria, by force if necessary, part of the French colonial empire in Africa that they were unwilling to grant independence, but the Algerians successfully fought back, starting the spread of emancipation from multiple former African colonies, while stylistically, featuring so much archival footage, the film this most resembles is Chris Marker’s The Grin Without a Cat (Le Fond de L’Air Est Rouge) (1977).

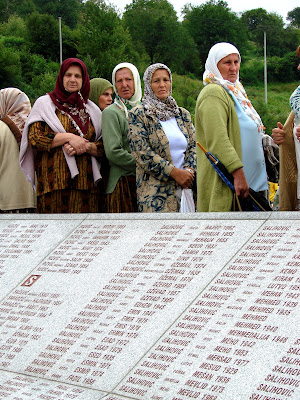

Johan Grimonprez is a Belgian multimedia artist, filmmaker, and curator who studied anthropology, photography, and mixed media at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Ghent, receiving a Masters in Video and Mixed Media at the School of Visual Arts in New York, now teaching at the Belgian Royal Academy and the Film Institute in Amsterdam. A child of the 60’s, he describes his films as “an attempt to make sense of the wreckage wrought by history.” Known for his critical view of media, corruption, and propaganda, situating themselves at the intersections of art, cinema, documentary, and fiction, the critically acclaimed films and video installations of Grimonprez explore the mechanisms by which fear and ignorance are perpetuated and whipped up in the media. Informed by a wealth of fully documented media sources, spending eight years researching the film and four years editing it, his work explores the tension between the intimate and the bigger picture of globalization, suggesting history has been infected by fear, which has tainted the political and social dialogue, providing instead new narratives to tell a story, where his work emphasizes a multiplicity of realities. With that in mind, this video essay film is about the promise of decolonization, the hope of the Non-Aligned Movement and the dream of self-determination, yet it is also about the multinational corporations working hand-in glove with the military-industrial complex to smother this very dream. In a choice that might seem perplexing to some, jazz musicians are as prominent as the historical realities, featuring the distinguished voices of Abbey Lincoln and Nina Simone, along with some of the giants of jazz, Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Dizzy Gillespie, John Coltrane, Thelonius Monk, Charles Mingus, Eric Dolphy, Art Blakey, Ornette Coleman, Archie Shepp, Max Roach, Pérez Prado, and Melba Liston, among others, with Armstrong and Dizzy Gillepsie sent to Africa on a good will tour as Jazz ambassadors by the State Department, following earlier trips to the Soviet Union in the 50’s, spreading American values worldwide, though some might describe it as propaganda countering the influence of the Soviet Union during the Cold War. Playing to more than two million Africans, with newspaper photos following the tour, they found themselves in the eye of the storm, peddling freedom while behind the scenes a myriad of westernized forces led by Belgium, Britain, and the United States, were undermining that very concept from being born in Africa, conspiring to assassinate one of the leading lights of the decolonial movement in Lumumba. In September 1960, the Congo had entered the UN world body together with 16 other newly independent African countries, but on February 16, 1961, a month following Lumumba’s betrayal, Abbey Lincoln, Max Roach, writer Maya Angelou and 60 others crashed a UN Security Council meeting in protest of Lumumba’s murder, seen combatively fighting with security, while Belgian embassies around the world came under assault, with demonstrators pelting them with eggs or setting fires, where the hypocrisy of this heinous act was on full display around the world. President Eisenhower, in an attempt to restore America’s image abroad, sent these jazz ambassadors to Africa, hoping to quell the storm, but when Louis Armstrong realized they were being duped, unknowing decoys in the CIA’s assassination plot, he got on the first plane home, back to a country where racial segregation was still enforced by the law. Perfectly encapsulated by Allen Dulles, the director of the CIA, seen casually smoking his pipe, not to be confused with his older brother John Foster Dulles, who was Secretary of State at the time (with an airport named after him), with one brother sending the jazz musicians as camouflage while the other was concocting a murderous coup, this barrage of mixed messaging is an atypical yet clear-eyed interrogation of Western powers’ murderous collusions under the guise of liberal values, giving viewers a distinct view of just exactly what this meant at the time, where the effects of nation destabilization are still being felt today, as you can draw the parallel with current genocides in Rwanda, Sudan, Gaza, and Yemen. In Belgium, no one investigated their complicity in Lumumba’s murder for over forty years, establishing a parliamentary inquiry in 2001, classifying his murder as a war crime, concluding that Lumumba could not have been assassinated without the complicity of Belgian officers, backed by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency, with Belgium bearing a ‘moral responsibility’ (Report Reproves Belgium in Lumumba's Death), leading to an official governmental apology in 2002. To this day, there still isn’t much resource material available. The film is a refresher course on geopolitics, as even sixty years later, armed groups continue to roam the countryside in the Congo threatening ordinary citizens, where according to a 2023 Amnesty International report (Human rights in Democratic Republic of the Congo):

Persistent large-scale attacks against civilians by armed groups and the Congolese security forces fuelled the humanitarian crisis in which nearly 7 million people were internally displaced and thousands of others fled the country. Armed groups killed thousands of civilians, and the army carried out extrajudicial executions. Sexual and gender-based violence remained prevalent, with over 38,000 reported cases in Nord-Kivu province alone during the first quarter of the year. The rights to freedom of expression, peaceful assembly and association were routinely violated. Journalists, opposition members and activists, among others, were subjected to arbitrary detention and faced unfair trials. Mining projects in Lualaba province led to the forced eviction of thousands of people from their homes and livelihoods, while Indigenous Peoples faced eviction in the name of conservation.

Not unlike Swedish documentary filmmaker Göran Olsson’s The Black Power Mixtape 1967 - 1975 (2011), this film encourages thought-stimulating concerns about the international order and the way in which media and music shape our cultural worldview. Some films have explored these subjects before, like Djibril Diop Mambéty’s Hyenas (Hyènes) (1992), Peter Bate’s CONGO: WHITE KING, RED RUBBER, BLACK DEATH (2003) or Hubert Sauper’s We Come As Friends (2014), where the dominant capitalistic interests are so overwhelmingly in favor of corporate interests like the oil companies, yet they hide their true objectives behind puppet African figureheads who have been given titles and positions of prominence in African “corporations” that have been formed only to bypass laws designed to exclude outsiders from obtaining controlling interests in what are African resources. Initially there were two Congos, where one was a former French colonial area, while the other was the former Belgian colony. African directors Mambéty and Ousmane Sembène were extremely suspicious of Western colonialist values and its allegiance to materialism corrupting the African shores since independence in the 1960’s, with Mambéty providing the central thrust of his film, suggesting Africans are “betraying the hopes of independence for the false promises of Western materialism… We have sold our souls too cheaply. We are done for if we have traded our souls for money.” Oreet Rees and Pippa Scott’s KING LEOPOLD’S GHOST (2006) exposed the systematic atrocities from Belgium’s 19th and 20th century colonial intrusion into the Congo, becoming the personal domain of Belgian King Leopold II, where they burned and destroyed up to a hundred local villages for rubber plantations, shooting anyone who disagrees, imprisoning the villagers for slave labor, kidnapping the wives of the working men, then cutting off the men’s hands if they resisted or if what they produced was too small, where the history of atrocities is horrendous, yet the underlying method behind this madness was purportedly “bringing civilization to the uncivilized.” Instead they brought murders and mutilations, which have been historically passed down to subsequent generations, along with a swath of destroyed villages. You may squirm when you hear then Belgian Prime Minister Gaston Eyskens literally speak of an inferior race of people while also claiming Belgium’s colonization of the Congo was “not to satisfy colonial or imperial aspirations but to complete a mission of civilization.” This film also introduces the dark figure of Moïse Tshombe, a man Malcolm X described as “the worst African ever born,” a backstabbing Congolese official accusing Lumumba of communist leanings and dictatorial rule, leading a secessionist movement splitting the lucrative Union Minière mines Katanga region from the Congo solely for monetary gain, with the full support of Belgium who wanted to secure their interests, flying in paratroopers and surrounding the mines with paramilitary forces. However, it was America’s rejection of Lumumba that forced his government into turning to the Soviet Union for help, as he inherited a disaster, with the Belgians emptying the coffers of the fledgling state and making sure the Congo never had a chance to develop, as they never trained their replacements, but just left in masse, with resignations in droves, leaving more than 25% of the country unemployed, having little other recourse due to the fragile nature of forming and running a government in a new nation, where allies and resources are essential. The crisis that engulfed the Congo, impossibly complex, increasingly brutal, ended with a military coup and the three-decade rule of Joseph-Désiré Mobutu, a onetime Lumumba ally who went on to govern as a ruthless Western client. The death of Lumumba, brought down by a combination of Congolese politicians, Mobutu’s army coup, and Belgian “advisers,” with the tacit support of the CIA, the British M16, and the malign neglect of the United Nations, was a signal moment of both the Cold War and decolonization, two defining events of the postwar world, where Lumumba’s story, as depicted in the film, is the story of how they became inseparable, while also providing an expansive view of how the last vestiges of American imperialism, with its policy of meddling in the affairs of others, exactly as they were doing in Vietnam, literally destroyed Congo's hopes for independence. Along with Mati Diop’s Dahomey (2024) and Raoul Peck’s Ernest Cole: Lost and Found (2024), we are constantly reminded that the deplorable impact left behind by colonialism is still with us today.

Even after all these years, it’s simply amazing what was happening at the United Nations in 1960, given prominent exposure on the international stage, as world leaders routinely met on the biggest stage and actually discussed how to solve world problems, something that would seem unthinkable today, as the organization has been stripped of all power and significance, reduced to little more than clerical duties. One of the stark revelations of the film is how Russia’s Nikita Khrushchev and Cuba’s Fidel Castro were viewed at the time as enemies of freedom and democracy, yet it is actually the Americans undermining the democracy movement in Africa, while Russia and Cuba, along with a host of African and Asian nations, were actually aligned against the colonial powers, namely Belgium, Britain, and the United States, in support of Africa’s attempts to break free from the devastating effects from centuries of colonialism plundering the resources of the African continent by brutality and force, with the CIA financing resistance armies that raped, killed, tortured, imprisoned, and mutilated African citizens who fought for freedom, assassinating democratically elected leaders, then installing puppet regimes to carry out policies that benefited their exclusive interests. It’s rare to see Patrice Lumumba, Fidel Castro, and Malcolm X united in solidarity with Nikita Khrushchev. It’s the 1950’s Cold War, anti-communist playbook that we’ve seen before in the 1953 Iranian coup d'état, overthrowing an existing government that was preventing the flow of oil to the wealthiest nations like Britain and the United States, imprisoning the Prime Minister, placing him under house arrest, while installing the Shah of Iran, who eventually became a ruthless war criminal, or in Chile in 1973 with Salvador Allende, with the CIA assassinating the first Marxist to be elected president in a liberal democracy in Latin America, then installing Augusto Pinochet as president, a ruthless dictator for twenty years who was ultimately charged with a litany of war crimes, with similar shenanigans also happening in Guatemala and the Dominican Republic. Yet this film focuses on Patrice Lumumba in 1960 immediately after obtaining their colonial independence from Belgium, a high profile leader who was simply extinguished for political expediency, reflective of how the world viewed blacks at the time, still believed to be inferior and subhuman, so his murder was seen as acceptable by agents acting on behalf of the CIA, the Belgium government, and the blatant neglect of the peacekeeping United Nations Operation in the Congo under UN Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld (impossible to believe today, but he held one of the most powerful positions in the world at the time, commanding international respect), with the West labeling him a communist, a completely false accusation, but this demonizing and stigmatization allowed them to bulldoze over his pan-African beliefs, envisioning a unity of African nations, voicing his concerns at the independence handover ceremony, “We who suffered in our bodies and hearts from colonialist oppression, we say to you out loud: from now on, all that is over.” This African solidarity was viewed as a threat to the West, with Lumumba replaced by a puppet government under Joseph-Désiré Mobutu, who was a notoriously corrupt autocrat, amassing millions in personal wealth at the expense of the economic deterioration of his own country, where a brutal war left millions dead, using rape as a weapon of war, yet he was more sympathetic to Western interests, where the historic flow of colonial mining interests could continually be extracted out of Africa to the West, where it’s safe to say that not one Congolese has benefited from the wealth extracted from those mines except the kleptocracy running the country. Countered by footage of Eisenhower’s public promises not to interfere in the policy of the Congo, the extent of just how much the United States resorted to lies and dirty tricks to covertly undermine newly formed democracies abroad is staggering.

One of the other revelations is bringing to light an enigmatic figure that is barely known, remaining on the periphery of historical narratives that privilege the so-called founding fathers of African independence, with the film re-introducing Andrée Blouin, a mixed-race Congolese woman who threw herself into the fight for a free Africa, an activist and writer, as well as a dynamic, charismatic speaker, mobilizing the Democratic Republic of Congo’s women against colonialism, singlehandedly enrolling 45,000 people into the Congolese Independence Party, heading the women’s wing of the party where she worked to expand literacy, fight alcoholism, and for women’s and children’s rights, rising to become a key adviser to Patrice Lumumba, actually trading ideas with famed revolutionaries and legendary postcolonial leaders like Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah, Guinea’s Sékou Touré, and Algeria’s Ahmed Ben Bella. These relationships led the European press to denigrate her as a shadowy communist and “whore,” often called the “Mata Hari of Africa,” a courtesan of powerful African politicians, completely representative of the historically racialized and sexualized representations of women of color in politics, belittling her intelligence and widespread influence, yet in the same breath she is also described as “the most dangerous woman in Africa,” much as the FBI’s J. Edgar Hoover in 1962 labeled Martin Luther King as “the most dangerous and effective Negro leader in the country.” She experienced first-hand the deadly effects of racism at the hands of French colonizers, raised in an orphanage where she endured years of starvation, torture, and imprisonment, fleeing the orphanage at 15 to defy an arranged marriage, but it was as a young mother when the French colonial administration refused to allow her 2-year old son access to quinine, malaria medicine, claiming it was for Europeans only, an ill-fated decision that left her son dead within days, a traumatizing event that led to her radicalization, concluding that colonialism “was no longer a matter of my own maligned fate but a system of evil whose tentacles reached into every phase of African life.” What little we see of her onscreen is utterly fascinating, as all the other leaders are men, where she is viewed as the woman behind Lumumba, serving as his speechwriter, Chief of Protocol in the new government, and diplomatic liaison to European governments, yet her intelligence and profound influence are unmistakable, taking part in multiple struggles for independence across Africa in the 1950’s and 1960’s. At the time of Lumumba’s arrest, Blouin was sentenced to death as well but was able to flee the country, leaving her children behind, relocating to Algiers and later Paris. While in exile, soldiers looted her family home and brutally beat her mother with a gun, permanently damaging her spine. She wrote her own personal memoirs, My Country, Africa: Autobiography of the Black Pasionaria, published in 1983, an excerpt can be read here: How the West Destroyed Congo's Hopes for Independence, but it’s been out of print for decades, republished earlier this year following the release of this film, where cinema, much as it did with Pamela B. Green’s Be Natural: The Untold Story of Alice Guy-Blaché (2018), or Madeleine Hunt-Ehrlich’s The Ballad of Suzanne Césaire, is exposing forgotten and long-neglected female historical figures who were automatically assumed to be less important than the male figures surrounding them, whose contributions never received their due during their lifetimes.

Where Jazz & Espionage Collide | Soundtrack to a Coup D ... Greg Lemley video interview with director Johan Grimonprez from Inside the Arthouse, YouTube (42:32)