|

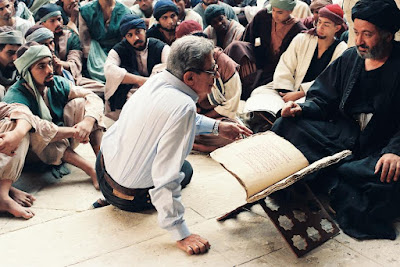

| Director František Vláčil on the set |

|

| Writer Vladislav Vančura |

MARKETA LAZAROVÁ A Czechoslovakia (162 mi) 1967 ‘Scope d: František Vláčil

The tale was cobbled together almost at random, and hardly merits praise. But no matter. The douser’s rod continues to quiver over the waters hidden below. —opening narration (Zdenĕk Štĕpánek)

A sweeping, widescreen black and white 13th century historical epic, voted the best Czech film ever by a survey of Czech film critics in 1998 on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of Czech cinema, some truly spectacular imagery by Bedřick Bat’ka, endless snowy landscapes, most notably a pack of black wolves running through the snow, original Medieval sounding chorus music written by Zdeněk Liška which throbs throughout with a soaring soprano, like an unseen heart, The Beginning of Marketa Lazarova YouTube (3:26). This is the kind of movie that could only be made in the oppressively bleak atmosphere of Eastern Europe, as the nightmarish misery index is astronomical, like watching the Crusades or the Spanish Inquisition, where what we bear witness to is endless slaughter. A truly heartless story of two rival families, the pagan Kozlíks (Josef Kemr) in Roháček, typically seen cracking a whip, and the Christian Lazars (Michal Kožúch) in Obořiště, who are nearly indistinguishable, as both appear equally cruel and tormenting, though the Kozlíks are described as having more sons than sows, abducting one of the King’s family, Kristián (Vlastimil Harapes), Marketa Lazarová (1967) - The Capture of Count Kristian by Kozlik's Sons YouTube (41 seconds), the kidnapped victim then falls in love with one of the wildly earthy daughters, Alexandra (Pavla Polášková), initially seen butchering an animal with an ax, from the beginning, a doomed love affair. Both rivals end up fighting each other as well as the King’s troops, yet when the Kozlíks send one of their sons to request help from the Lazars in fending off the royal troops, he is nearly beaten to death, so the Kozlick’s retaliate by wiping out the entire family and kidnapping Marketa, an unbelievable performance by Magda Vášáryová (who served as the Slovak ambassador to Austria in the early 90’s, becoming a liberal anti-nationalist politician, even becoming a Slovak candidate for the presidency in May 1999), who plays the innocent, virginal daughter who has been promised by her father Lazar to the convent, the epitome of Christian kindness and humanity, Marketa Lazarova - "Introducing Marketá" scene {Frantisek Vlácil, 1967} YouTube (1:25), a complete contrast to everything else seen on screen, which appears vile and dirty, rotten to the core, except Marketa. But she becomes the lover of the kidnapper Mikoláš (František Velecký), more like his slave, knowing no other protector, all have abandoned her, as her family was eliminated during her capture, her father crucified to the entrance fence of her family’s fortress. Evil is everywhere. But the King’s Sheriff, Captain Pivo (Zdenĕk Kryzánek), under German Christian rule, decide to hunt down the evil-doers, which results in a ferocious, mass slaughter, humanity becomes unhinged. Hell raises its weary head. In an extraordinary transformation, the earthy daughter plunges a rock to her lover’s head after his King wipes out her family, so much for love, and Marketa is led to the convent, nuns are arranged like paintings on the walls, a ritual of God’s peace and forgiveness is rejected, unbelievably she returns to be married to her kidnapper in his last, dying breath while carrying his child, yet she has become transformed into pure evil, with nowhere to wander in the desolate, wintry countryside except with a simpleton friar named Bernard (Vladimír Menšík) with a flair for Biblical verse (a cinematic invention, as he is not in the novel), who chases off after a goat instead of tending to Marketa, who wanders alone, seemingly forever.

Milos Forman’s Loves of a Blonde (Lásky jedné plavovlásky) (1965) and Jirí Menzel’s CLOSELY WATCHED TRAINS (1966) achieved critical acclaim in America, with Menzel’s film winning the Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film in 1968, while Vláčil’s film was not released in the U.S. until 1974, in a severely edited version, shortened by more than an hour, that received mixed reviews. Unlike other directors of his generation, Vláčil did not attend FAMU, the Prague Film School, and instead studied art history and aesthetics at Masaryk University in Brno, working on animation and educational films, actually animating Eisenstein’s BATTLESHIP POTEMKIN (1925) frame by frame, while much of his early work was in painting. After a stint in the army working in the film unit, his short film GLASS SKIES (1958) won an award at the Venice Film Festival. Coming shortly after Tarkovsky’s 15th century epic masterpiece ANDREI RUBLEV (1966), featuring rival princes and a Tartar invasion, also a muted Holy Fool female character Durochka (Irma Rausch) who silently witnesses the annihilation, utterly traumatized by what she sees, this film in many ways mirrors that film, where Marketa, always suffering silently, is a stand-in for that Holy Fool character, where her expected religious ascension into the nunnery takes a perverted twist, psychologically pulverized by the slaughter she witnesses, as her trauma transfers directly to the audience. Like witnessing something out of a Pieter Bruegel the Elder painting, this film takes us back even further to the middle of the 13th century, using cryptic chapter headings introduced by the sarcastic voice of an omniscient narrator (Zdenĕk Štĕpánek), though there appear to be shifting perspectives, giving this a storybook feel, where much is told through monologues, dream sequences, and extensive flashbacks, creating a mystifying landscape of utterly breathtaking visual imagery, yet part of the confusion of the film is finding ourselves in the middle of such an alien culture, where we have no idea what the people are up to, what motivates them, or why they act the way they do. Vláčil has no intentions of helping the viewer out, presenting a rather bleak view of the human condition, creating an uncompromising vision of a menacing world where nothing makes sense, immersed in threats, intimidation, betrayal, and trickery, where all we really understand is the primitive nature of an unforgiving landscape, where violence is the language of choice, letting their actions speak for them. Having worked on the film for six years, where clothing designer Theodor Pištěk painstakingly researched the authenticity of the costumes, which were hand-sewn, it is part of a trio of historical dramas set in the Middle Ages that began with THE DEVIL’S TRAP (1962) and concluded with VALLEY OF THE BEES (1968), which was filmed before this film was released, using many of the same costumes and decorations. Inspired by the avant-garde novel by writer Vladislav Vančura, the first chair of the experimental Devětsil group, first published in 1931 (not published in English until 2016), just 13 years into the existence of Czechoslovakia, created out of a negotiated settlement following WWI, it was awarded Czechoslovakia’s State Prize for Literature for emphasizing the poetic and experimental use of language. Vančura was a perennial outsider, a key figure in Czech Modernism, becoming a symbol of cultural and political resistance as a communist who joined the anti-fascist resistance movement against the occupying Germans, captured and tortured by the Gestapo in Prague, and eventually executed by firing squad in 1942, so adapting his work could be viewed as a political act of rebellion. The novel is a medieval epic set in an unspecified time, yet Vláčil deliberately chose the 13th century, attempting to project himself into the mindset of an earlier age, much like Bergman in The Seventh Seal (Det sjunde inseglet) (1957) and THE VIRGIN SPRING (1960), yet it also evokes comparisons with Kurosawa’s SEVEN SAMURAI (1954), with Vláčil claiming the film’s final structure was very close to that of Janáček’s Sinfonietta, Leoš Janáček - Sinfonietta (1926) - YouTube (24:19), an ode to Czechoslovakia, with its military bands, fanfares, and cinematic jump cuts, still sounding new nearly 100 years later.

Divided into two parts, Straba, a male character from pagan Slavic mythology, with motifs of cruelty and damnation, and Lamb of God, the regenerative power of love and foundational message of Christianity. The theme of paganism, represented by Kozlík’s clan, permeates the first part, while a failed religious transcendence, embodied by Marketa Lazarová, dominates the second, suggesting a time when Christianity was on the rise, yet there were pockets where paganism still exists. While there are frequent references to God, along with quotations and examples from the Bible, much of the film was shot in winter, evoking its own unique brand of cruelty, where the bleakness of the times truly suggests the Dark Ages, with characters dressed in furs or animal skins, yet it was a period when Bohemia became one of the most important powers in Europe, with the development of towns and agriculture, and the movement of Germans into the Czech lands, taming the wild frontier in much the same way that it’s portrayed in the American Wild West. However, the film is not a history lesson, nor is it an allegory on the present, as it offers no foreseeable resolution, void of any moral or ideological messages, as people remain imperfect, motivated by primitive instincts, passions, and fears, though perhaps similarities could be drawn between the dogmatic rigidities of Stalinism and Christianity, or between the Christianization process occurring during the 13th century and the Sovietization of Eastern Europe. Instead it’s more of a psychological immersion into the mindset of the times, exploring the constantly shifting interplay between characters with frequent jumps in time and place, accentuating the striking use of widescreen composition, while offering few concessions to convention. The liberalization of the Communist Party in the 60’s allowed for this adaptation, as many writers and filmmakers reasserted the need for art to become a prominent aspect of the prevailing culture, with the film emerging a year before the Prague Spring. Much to the surprise of most, Vláčil adapted what was viewed as an unadaptable literary source because of the thematic and compositional complexity of its literary structure, offering darkly humorous musings and wry commentary by the narrator, who poses his own existential quandaries throughout the story, establishing a relationship with the reader, yet what the director instead chose to accentuate is the artistic value of a uniquely personalized aesthetic, creating an experimental film, with an unorthodox structure, and a variety of different narrative techniques, expanding on the source material while offering completely new meanings. Cowritten by the director with František Pavlíček, a playwright and theater director, also a Slavic literature student, it took four years to write the screenplay, which was not completely finished when shooting began. Perhaps most strange, the director actually had his cast live a medieval life in the Šumava forest for two years before filming began in order to better comprehend the 13th century mindset, “There we lived like animals ...lacking food, and dressed in rags. I wanted my actors to live their parts.” It was the most expensive film of its day, yet generated barely a blip on the radar when it was released, with the studio expressing reservations about the ever-growing budget, also the stubborn attitudes of the director, but special leeway was granted due to the position Vláčil occupied as an “auteur,” remaining the principal artist and creator of the film, which was not new in Czech film, as evidenced by the cult-like status of František Čáp and Otakar Vávra in the 30’s and 40’s, though Čáp was eventually banned from directing by the postwar Communist regime and resumed his career elsewhere, so the concept of freedom of expression was limited. While the film was listed at #154 on the 2012 BFI Sight and Sound Critics’ Poll of greatest films, Votes for MARKETA LAZAROVÁ (1967), it was completely left off the more recent 2022 Poll, suggesting a falling out of favor, while Věra Chytilová’s surreal Czech New Wave classic DAISIES (Sedmikrásky) (1966) climbed from #202 in 2012 to #28.

In the beginning of the second section, Bernard’s existential monologue is actually addressing the film’s narrator, a highly ingenious technique rarely seen, while the narrator acridly admonishes him for his sexual relationship with a sheep, “You know she is no woman, as you are no lamb.” In much the same way, dubbed offscreen dialogue often interacts with the action onscreen, with frequent flashbacks also blurring the lines of reality, often interwoven with real-time scenes, taking a relatively simple story yet adding layers of obfuscating complexity, often told out of order, focusing almost exclusively on destructive events, making this difficult viewing despite the artful aesthetic. There is a lengthy narrative passage told by Kozlík’s wife, Lady Kateřina (Nada Hejna), who incidentally acknowledges a higher power and believes in the Lord, frequently chastising her husband for his lawlessness, describing in great detail the childhood of Mikoláš, where he was left to fend for himself among the wolves, describing the mythological history of the Kozlík clan’s ancestry, remaining closely connected to wolves, as they personify the pagan or animal spirit, with all its cruelty and ruthlessness, remaining outside all social conventions, MARKETA LAZAROVA (1967) - Wolf Among Humans YouTube (6:21). The Middle Ages was a time when humans and animals lived side by side next to each other, and becoming animal-like was viewed as both a threat and a possibility, while the Lazars embraced and were associated with a new religion. As a counterpoint to this often disjointed narrative structure, Vláčil uses a mirroring visual aesthetic, where images of magic and eroticism may emerge, blending extreme close-ups while also capturing a distant space, altering the focus of the frame in dramatic ways, as the camera is almost never still, which may be an attempt to match the unorthodox structure of Vladislav Vančura’s novel, suggesting life in the Middle Ages may have been cruel and barbaric, but it was also authentic. The Kozlíks and Lazars represent the primal instincts of mankind and are nomadic in nature, moving with the seasons, where freedom is represented by their murderous impulses, with both families preying upon the innocent, especially in winter, becoming marauding bandits that take what they want, essentially believing that anything passing within their geographical boundaries belongs to them, where it’s questionable whether it’s too early for civilization to intervene, or whether the wildness of nature will continue to rule long after the film ends, while the conflict between paganism and Christianity is paralleled by the conflict of centralist rule and anarchy. Vláčil’s film exerts no ideology, and instead captures the raw and drastic aspect of the times in a highly original manner, immersed in dark, low-key lighting, as if unable to escape from the shadows, drawing upon remote historical references to create a film with surprising contemporary impact. The one and only time Marketa and Mikoláš have a conversation takes place in a relaxed manner while lying under a canopy of trees, telling an allegorical tale that mirrors the door closing to Marketa’s convent, as Mikoláš speaks about stags fighting over female does, who mate for life, and recalls seeing an injured stag, as accompanying images of animals appear in a forest. “His antlers were bigger than branches. He looked at us without fear. Kozlík motioned for silence. We went closer. It moved away, and we went after it. Below the hillside there was a bare plain. Grass, stones, lichen. This valley was more wretched than a cemetery. Bones, limbs, a thousand antlers on white skulls. He stood alone in the middle. Defeated, alone. Alone. Kozlík whispered, ‘Look, the solitude of death.’” For a couple of seconds the stag stops moving, and so does the film, instead becoming a stark photograph, like something we might see in Chris Marker’s La Jetée (1962), as the stag stares at us from the screen, frozen in time. This is the closest the film comes to the book’s existentialism, as death is perceived the same way it is approached in the novel, as a hollowness, a void. It should also be stated that existentialism was one of the artistic movements panned by Communist propaganda as “bourgeois art” because it subverted the collective norms sought after by the Communist dictatorship. When viewed today, we might read the gloomy hostility and bitter words about sovereign might, soldiers, and cruel customs of earlier times as expressions of a healthy distrust towards any authority, such as those who governed empires and led the nation into a long-lasting history of bloodletting.

Markéta Lazarová (1967) EN - YouTube Criterion HD film with English subtitles (2:45:28)