|

| Anpo protests, 1960 |

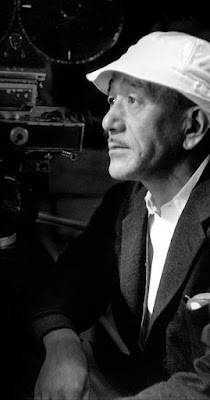

LATE AUTUMN (Akibiyori) B Japan (128 mi) 1960 d: Yasujirō Ozu

People complicate the simplest things. Life, which seems complex, suddenly reveals itself as very simple. I wanted to show that in this film. There was something else, too. If needing to show drama in a film, the actors laugh or cry. But this is only explanation. A director can really show what he wants without resorting to an appeal to the emotions. I want to make people feel without resorting to drama. And it’s very difficult. In Late Autumn, I think I was really successful. But the results are still far from perfect. —Yasujirō Ozu, Film Comment, On Yasujirô Ozu

A somewhat comic story of family meddling, where the life of an unmarried daughter is the primary focus, with friends of the family insisting that she marry before it becomes too late, with three middle-aged men trying to get the young woman married through their own somewhat inept arrangements, which seems to be more about gossip and rumors than anything else, as the director retreads on similar themes initially raised in Late Spring (Banshun) (1949), yet inverting the parental gender roles, examining the consequences of marriage from a mother’s perspective, yet by 1960, this is an old-fashioned and extremely conservative viewpoint, resorting to pre-war methods of arranged marriage, which may explain why the mocking tone is one of comic bemusement. Accentuating still-existing patriarchal dominance in society, featuring men in business suits nosing into a friend’s family affairs, usually centered around communal discussions over shared sake, as their bumbling incompetence leads to awkward situations and misdirected family tensions, but somehow, someway, it all works out happily in the end, but this time, instead of Chishū Ryū staring off into the distance into his solitary future, it is Setsuko Hara, having married off her lone daughter, leaving her all alone at the end to contemplate her own solitary existence, with shots of empty rooms and office corridors that were once populated with people as metaphors for the emptiness in the next phase of her life. While this is among the last films Ozu directed, it is an adaptation of a 1960 story written by Ton Satomi, the pen-name of Japanese author Hideo Yamanouchi, unafraid to add a little toilet humor, as one of the characters, an elderly widower, always rushes off to the bathroom every time he gets excited about the prospects of remarrying. Essentially a comedy of manners exploring how women still live in a patriarchal society, as men, 15-years post-war, even after the instillation of new democratic laws and reforms, still hold the power to decide what happens in women’s lives, even when presented as modernized and self-sufficient in a new economically revitalized Japan. While Ozu reduces this to comic absurdity, nonetheless the point is made that women are free from masculine authority, but only in spirit, as all the power in institutions, namely government, law, education, business, finance, and professional organizations continue to be male-centric, suggesting the choice of romantic love is a luxury few can afford, that it is folly to attempt to cling to the old ways in a world so insistent upon changing, yet the newer generation’s options come with its own perils, forced to choose between independence and the restrictive safety of marriage. Interestingly, Ozu shows a dozen young men and women assembled for a hike through the mountains walking in step through the fields, which mirrors the opening of Hou Hsiao-hsien’s Good Men, Good Women (Hao nan hao nu) (1995), with men and women walking through the countryside singing songs, yet Ozu also adds the sound of a girl’s choir at a gathering of young students at a hot springs retreat, becoming a poetic narrative device, accentuating the theme of autumn leaves falling, a reference to the changing times, offering the mindset of the mother as her daughter is about to be married, bringing to an end one phase of motherhood. Contrast that with the sounds of Mozart Piano Sonata No.11 in A Major K.331 (Mov.I - Andante grazioso) YouTube (13:44) heard being played off in the distance while a dressmaking class is in session where the mother works, shifting quickly to the sound of typewriters where the daughter works in an office, yet unlike her mother’s generation, she doesn’t need to marry as she has her own means of supporting herself, another example of a generational shift. In Early Summer (Bakushû) (1951), the choice made by the daughter, Setsuko Hara, flew in the face of tradition, defying the wishes of her family, ignoring their marital suggestion, and made her own choice, asserting her own future. Japan was transforming so rapidly, politically, socially, in terms of technology, in terms of lifestyle, as the country moved from being a military tyranny in the 1930’s, when Ozu was in the early part of his career, to becoming a liberal democracy in the 1950’s and 60’s, so, with that as a background, it’s no surprise that the way a parent lives, thinks, and feels is totally different to how their son or daughter does.

1960 was a year of protest and dissension against the renewal of the Japanese-American Security Treaty, which allowed the U.S. to maintain a military presence on the island of Japan, even after the end of the American occupation, a condition of restoring Japan’s sovereignty as a nation. Known as the Anpo protests, they were the largest popular protests in Japan’s history, including violent clashes between students and police, chanting anti-American slogans and singing protest songs, with over 10,000 students protesting, resulting in a series of recurring incidents throughout the year that placed a negative light on the treaty. Later in the year, a right-wing teenage fanatic assassinated a Socialist leader on national television, while later committing suicide in jail. None of this social turbulence can be seen in Ozu’s film, ignoring it completely, as if existing in an alternate reality. Portraying a tranquil society that no longer exists, this is not among the upper echelon of Ozu films, as the story itself feels slight, suffering from the stark contrast of having been done so much better a decade earlier in Late Spring (Banshun) (1949), with Setsuko Hara playing the daughter in that film, now playing the widowed family matriarch, though this film expands the viewpoint of young women during Japan’s modernization. The film opens with a memorial service on the seventh anniversary of the death of a late college friend, Miwa, as three middle-aged friends and former college mates, Mamiya (Shin Saburi) and Taguchi (Nobuo Nakamura), two businessmen, and Professor Hirayama (Ryūji Kita) greet Miwa’s widow Akiko (Setsuko Hara) and her 24-year-old daughter Ayako (Yōko Tsukasa), with all three of them once having a crush on the mother when she was younger. Mocking the chauvinism of the older generation, these three men serve as a kind of outdated Greek Chorus whose patriarchal influence is increasingly irrelevant as they remark upon Ayako’s beauty, quickly deciding they immediately need to find a marital match for her, which they arrange like a business deal, while also commenting on how attractive Akiko has remained. When these men return to their own homes, the comic exaggeration continues, displaying a comedy of errors with Taguchi dropping his clothes behind him at random throughout his home while his wife dutifully picks them all up and places them on a hangar, while the wives relentlessly tease their husbands and the children mock the emptiness of their patriarchal authority, with Ozu accentuating their blatant independence. After Tagushi’s prospective suitor already has a fiancée, Mamiya offers one of his employees, Gotō (Keiji Sada), but Ayako, who enjoys wearing Western dress, with a short hairstyle, insists she’s not ready to get married, that she couldn’t be happier living with her more traditional mother, who teaches dressmaking, wearing old kimonos, as they remain close, travelling around the country together exploring different parts of the country. Ayako’s refusal causes plenty of confusion and conflict, but the trio of men refuse to let go, deciding she’s only holding out because her mother’s not married, as she doesn’t want to leave her alone, so they set out to offer Hirayama as a good match for Akiko, resuscitating his teenage interest in her, but they fail to realize the consternation this careless interference will cause, leading to quarrels and misunderstandings. When Taguchi visits Akiko, presumably to hatch their plan, he never gets around to mentioning it, as she’s consumed with thoughts of her dead husband, yet Mamiya thoughtlessly lets Ayako know about the plan, and she is indignantly shocked that her mother is considering remarrying, so when she questions her mother about it, she believes she’s keeping secrets from her, yet Akiko really has no idea what she’s talking about. Angered by her mother’s apparent unwillingness to be forthcoming, she storms out of the house in a huff and visits a colleague from work, Yuriko (Mariko Okada, a breath of fresh air, stealing every scene she’s in), a thoroughly modern young woman, hoping she’d be sympathetic, but she takes her mother’s position, stating “I’d let my mother live her own life,” suggesting she deserves happiness, believing Ayako is simply being selfish. Ayako and Yuriko often run to the roof of their office building to converse, as do many of the employees, often seen peering over the ledge just to watch the trains pass, yet also sharing hesitant views on marriage, observing that friends who do get married tend to become socially disconnected, with suggestions that giving up your freedom is a major sacrifice. Nonetheless, Ayako re-engages with Gotō once he’s introduced through her own friends.

Accentuating the transition from childhood to adulthood, and the tension between tradition and modernity, Ozu’s particular style of filmmaking shows the tiny, quiet details of everyday life, featuring long takes and low camera positions from Yūharu Atsuta using a 50mm lens, never focusing on a single character, never using flashbacks, never shooting subjective images of any kind, nothing to show what a character may be thinking or imagining, eventually rejecting all point-of-view shots, avoiding any human-level vantage point (which is why the camera is so low), while eliminating camera movement, fades, or dissolves. The documentary look of his films feels surprisingly similar from film to film, establishing an ordinary rhythm of life, allowing viewers time to reflect, from which we can extrapolate universal themes and values, yet there are empty spaces of still lifes, interiors, building facades, urban streets, and landscapes, often occurring between scenes, with an everpresent train sequence inhabiting every film. Working with his screenwriting partner Kōgo Noda, together they collaborated on twenty-seven films over a thirty-five year partnership, developing a special bond together, which grew out of a shared cinematic sensibility and a natural friendship. Ozu made only two films after this one, coming near the end of his life, where four of his final five pictures were reworkings of earlier movies he’d made, the last six shot in color, writing a half-comic drama about parenthood and marriage prospects that also laments how traditions are fading away in postwar Japan. The economic growth in Japan as it entered the 1960’s was a surge towards modernity, hosting the Summer Olympics in 1964 as the first Asian nation to do so, representing Japan’s symbolic rebirth after the devastation of World War II. Like many of the films she’s in, Setsuko Hara only really comes into play in the later scenes, gaining more screen time, exhibiting a fuller emotional range, becoming the dominant star that she was. This film playfully exhibits the adolescence of fully mature men, where the camaraderie of their college days has never left them, still enjoying the idea of pulling pranks. Ozu’s films document the changing expectations placed upon women in a more modern society, exemplified by Ayako and Yuriko, two working girls in Tokyo who are offered opportunities their parents could never dream of. While the two women have their own ideas and each approach marriage differently, they personify the transforming role of women in Japanese society. The focus of the film shifts to Yuriko when she discovers these men have taken advantage of Akiko through behind-the-back rumors and unintentionally created a family furor. She storms into a meeting with the three of them ready to lay the hammer on all three, exhibiting a fierce sense of moral outrage, offering scathing criticism for creating a division between Ayako and Akiko, standing over them and reprimanding them like disobedient children, which they meekly apologize for, but in doing so, she reveals essential information that was missed by these instigators, who quickly regroup and add Yuriko to their hatched plot, but not before she tricks them into eating in her family’s restaurant, ordering a generous meal along with plenty of sake to go around, as these men are secretly coerced into contributing to the family coffers, enjoying the ruse afterwards, recognizing the cleverness of this new generation. While taking perhaps their last trip together to the Ikaho hot springs, the focus returns to Akiko, who assures her daughter that she has her full support if she wishes to marry Gotō, who by all indications is a generous and level-headed young man with steady employment, but that she is not so inclined, wishing for her daughter’s happiness while reassuring her that she’ll be fine on her own. What’s clearly evident is that neither one knows the lengths the other is willing to go to on their behalf, which is an intriguing comment on both women. This generational contrast is evident, however, as her daughter has much more self-assurance in approaching a new age, while Akiko remains thoroughly connected to the past through her deceased husband, whose spirit has never left her, unable to move on from his presence. As she witnesses the ritual of Ayako’s ceremonial wedding photo, dressed in formal clothes, a send-off to a new phase in her life, Akiko returns home, briefly visited by Yuriko in a deeply affecting scene, with a montage of previously filled spaces now suddenly empty, rearranging things differently, folding her kimono, finally contemplating her solitary existence.