|

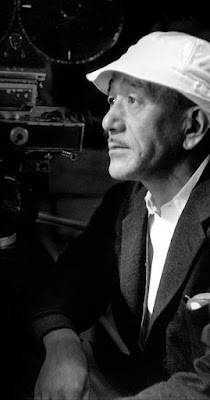

| Director Yasujirō Ozu |

TOKYO TWILIGHT (Tôkyô Boshoku) B Japan (141 mi) 1957 d: Yasujirō Ozu

A piercing portrait of family life, easily the most downbeat, melancholic, and melodramatic of Ozu’s films, a noir-influenced family drama that is also Ozu’s bleakest film, given a German Expressionist look, as if shot through a fog, like early Hitchcock films from the 20’s, such as The Lodger (1927), where the cheerfully ironic opening and closing music resembles what you might hear in a Fellini film, also used in a similar capacity during a funeral sequence of EARLY SPRING (1956). The lurid, somewhat sensational aspect of the material may have grown out of the criticism the director received that his films were out of touch with the youth of today, so a rebellious youth is fully integrated into this movie. Yet it was not a success, the only Ozu film not to make the top ten of the Kinema Jumbo poll since THE ONLY SON (1936), catching Ozu off-guard, where he and longtime co-screenwriter Kōgo Noda feuded, with Noda apparently unhappy with Ozu’s final screenplay, both viewing this film as a failure. Slow to accept new technical advances, this is Ozu’s last black and white film, shot by longtime collaborator Yūharu Atsuta under barely lit circumstances, most of it shot after dark, provocatively dealing with issues such as marital discord, rebellious adolescence, premarital sex, abortion, and suicide. In an era of Covid and the wearing of masks, this film is eerily striking with some prominent characters wearing face masks as protection from the contamination of pollution in the city, with much of this film taking place in seedy Tokyo neighborhoods. By any measure, this is a different kind of Ozu film, unlike any of his others, his only postwar film taking place in the dead of winter, where the lighting, in particular, accentuates shadowy figures walking late at night down darkly lit spaces, narrow alleyways, and the cramped quarters of small bars, mahjong and pachinko parlors, or noodle houses that dot the landscape, with nearly all the action taking place at night, or in shadowy interiors, offering a grim tone where the protagonists deal with the dissatisfactions in life, shockingly offering a psychologically downbeat subject matter haunted by an implacable shadow of death, where there are shady characters outside the family featuring plenty of drinking and gambling. There’s even a Robert Mitchum movie poster from the film FOREIGN INTRIGUE (1956) hanging on the wall in one of these dimly lit bars. It opens, however, in a wintry scene with the always sympathetic Shukichi (Chishū Ryū) taking a seat at a Ginza neighborhood sushi bar ordering a meal with some warm saki, as we see commercial buildings, power lines, and one lonesome street light illuminating the early dusk, with Tokyo viewed as a collection of neighborhoods with interconnected lives and stories, a city still in progress, a place and a people in flux, dislocated and often alone, though Shukichi lives in the more quietly traditional Zoshigaya district of Tokyo with two daughters, one obedient and one disobedient. His wife left some time ago for a younger man during the build-up to war, abandoning her children, with Shukichi concealing his grief, never burdening the children, sparing them the circumstances, though this film explores the ramifications of that concealment. The normally angelic Setsuko Hara appears in this film (her fourth Ozu film, the only one where her character is neither single nor widowed) as Takako, the elder daughter of Shukichi, in her most taboo-shattering role as an emotionally dispirited though proud young woman who leaves her abusive and alcoholic husband, bringing her 2-year old daughter with her, moving back into the home of her father, where she is obediently attendant to him, wearing traditional Japanese clothing. While there was also a brother who died in a mountain climbing accident several years earlier, Takako is unsettled and overly distraught right from the outset. When her father asks what’s wrong, she can barely say, overwrought with endless turmoil, carrying the weight of the world on her shoulders, never really having a moment’s reprise. When younger daughter Akiko (Ineko Arima), a college student, arrives home even later, she is sullen and noncommittal, completely rebuffing her father’s attempts to find out where she’s been, verging closer to open defiance and blatant disrespect. Shukichi is clearly exhausted with Akiko’s disobedient refusal to communicate, apparently unable to get through to her, where her impudence is an issue. Akiko’s not really in school any more, learning English shorthand instead, hanging out in bars and mahjong parlors late into the night, appearing surly and bad-tempered, never smiling, smoking cigarettes while acting nonchalant, a modern reflection of Western fashions and values, always dressed in a shabby, wrinkled coat, usually seen in search of her boyfriend Kenji (Masami Taura), who has been avoiding her, with people calling her derogatory names behind her back. By the time she catches up to him, she reveals that she’s pregnant, but he’s completely indifferent, expressing no interest whatsoever, even questioning whether the baby is his, the standard modus operandi for male denial that leaves her in a quandary. Offering a pitiless view of a Japanese family beset by repressed secrets and lies, there seems to be no end to the damage done, resulting not just in the fracturing of the Japanese family, but even more importantly, how individuals inexplicably blame themselves for the pain it causes. In no other film does Setsuka Hara look so world-weary and beaten-down as she does here.

A film that reveals the complex and often corrosive impact of American occupation, which serves as an unseen backdrop for all Ozu’s postwar films, where traditional Japanese ways of life struggled in contrast with the western imposition of modernist, capitalist, and thoroughly American consumer practices. Postwar Japan was a time when the Japanese identity was reconstructed under the influential gaze of American eyes to serve American interests. Young people of Japan in the middle of the twentieth century came of age during the rise of television and mass commercialized media, which was complicated and amplified by the leering presence of American military bases nearby, which helped change the face of Japanese society. This is the larger context underlying this lurid family drama. Of note, Shukichi tells Takako that he read her husband’s article entitled “Resistance to Freedom,” a rare protest against his country’s failure to question the magnitude of American commercial and political influence. Shukichi has a comfortable position working as a bank executive, meeting up for lunch with his sister Shigeko (Haruko Sugimura), who gets to work right away in finding marrying options for Akiko, believing this is her best option. It’s an interesting intersection of the old world meeting the new world, using an old world solution for a modern era problem, with Akiko resembling that 50’s juvenile delinquent so prevalent in American movies, like Nicholas Ray’s Rebel Without a Cause (1955), where teenagers are often viewed as socially maladjusted. Ozu applies the same principal here, as Akiko struggles with being raised without a mother, who has been presumed dead, but she runs into a woman purely by chance, Kikuko, (Isuzu Yamada, Lady Macbeth in Kurosawa’s THRONE OF BLOOD released earlier that same year), the proprietor of a mahjong parlor in the Gotando neighborhood, known for its unpaved roads and seedy bars, who was asking a lot of questions about her, knowing her entire family history, making her think this could be her mother. When they meet, it raises existential questions in her mind about where she came from. When Takako learns her sister actually rediscovered their mother, she quickly moves to protect her, paying the woman a visit while angrily informing her to never reveal she is actually Akiko’s mother. Yet when Akiko learns her sister paid a visit to the mahjong parlor, she immediately confronts her, suspecting something is wrong. Takako is forced to acknowledge their mother abandoned them at an early age to run off with another man, believing they would never see her again, while exhibiting shock that she actually turned up again in Tokyo. When Shukichi learns his brash younger daughter has been asking for money from relatives, he tries to speak with her, but Akiko is evasive, continually hiding the truth, as the money was for an abortion, something she could never speak about openly (though abortion was legal in Japan since 1948), sharing the truth with her sister, but the shame this would bring her father is a primary reason she could never be honest with him, so she invents excuses and little lies. That experience, however, leaves her emotionally drained, never fully recovering afterwards. When Shigeko pays a visit with her marital suggestions, her joyful mood quickly turns sour, as Akiko’s not the least bit interested, literally showing contempt for the idea. Because of her standoffishness, it is perceived as Western belligerence, seemingly wanting things her own way, where she’s such a disappointment to her father, who wonders how she turned out this way. Takako is the intermediary, always supporting her sister, identifying with her inability to find acceptance either within her family or in broader society, feeling like an outcast. Akiko begins doubting herself, questioning where she really came from, actually believing she is an outcast, that Shukichi is not her father, running back to Kikuko, expressing her own hatred for having been abandoned while demanding the truth, but she swears Shukichi is her father, once again leaving Akiko in a quandary, not knowing what to think, but never really feeling close with her father, instead feeling isolated and alone, which is never more apparent than when she is waiting in a bar for Kenji to show up, still waiting well past midnight, revealing a configuration of thick shadows in dark spaces, when a detective in civilian clothes (wearing a mask) picks her up and hauls her down to the police station, with Takako (also wearing a mask) coming in the wee hours to the station to pick her up. While not breaking any laws other than curfew (the same crime police use to haul James Dean into the police station in Nicholas Ray’s film), she is simply a young girl seen as being in the wrong place at the wrong time. Nonetheless, her father denounces her, claiming “You’re no child of mine,” while Akiko claims she’s not wanted, responding with “I should never have been born.”

A film described by critic Robin Wood as “the one nobody wants to talk about,” this is one of the very rare Ozu films in which laundry hung up to dry does not appear, recurring in every Ozu film from A Story of Floating Weeds (Ukigusa Monogatari) (1934), while trains, on the other hand, are still a staple, normally representing the possibility of movement and change, but here with overtones of melancholy or tragedy. With melodrama as the dominant element, Ozu stages an anxiety-ridden internalized struggle with the darkest realms, accentuated by bleak and somber settings, including a view from Tokyo harbor revealing smokestacks, industry, and the high cost of modernity, similar to Antonioni’s vision in RED DESERT (1964), described by Andrew Sarris as “the architecture of anxiety,” with a psychologically disoriented Monica Vitti suffering extreme alienation. In these depictions, the high cost of modernization equates to the loss of the human soul, which becomes fractured and less resolute. Featuring plenty of tearful scenes, this tragedy is juxtaposed against the calm demeanor of Chishū Ryū, a sympathetic figure who is the picture of fair-mindedness, with Setsuka Hara straddling the generational differences. Ineko Arima may get swept up not only by the unfortunate circumstances, but the massive influence of the major players she’s working with, coming across as abrasively shrill in stark contrast with their more measured restraint, yet Ozu along with Kōgo Noda have written a scenario where she dominates the screen time, accentuating the plight of the youth. More shaken than ever, Akiko wanders into a noodle house and orders sake, drinking it all down at once, sitting alone and beleaguered, then ordering another one. Purely by chance, Kenji walks in the door, once again pleading his case, justifying his own behavior, leaving Akiko little choice but to slap him hard in the face several times before walking out the door without uttering a word. Shortly afterwards a train whistle marks a significant event, with pedestrians running to the scene of a horrific accident, apparently throwing herself in front of an ongoing train. With her father and sister at her side in the hospital, she can be heard wanting to start over again, with Ozu curiously cutting to a clock and a yawning nurse, disaffected images that comment on the passing of time. Takako makes the journey to the mahjong parlor in her mourning clothes, informing Kikuko that she’s to blame for the death of Akiko, before leaving in a scene of repressed yet righteous anger. A cloud of sadness pervades in the aftermath of a needless death, with Takako suggesting her younger sibling missed not having a mother’s love, leaving her feeling abandoned and alone, while Shukichi, in re-evaluating the situation, feels compelled to acknowledge he always paid her more attention, to the point where he felt Takako might feel slighted, and apologized to his daughter for insisting upon the marriage that has caused such grief, depriving her from marrying the one she loved. After paying a visit to Takako’s husband, Shukichi realizes he’s not the same person, having become more irritable and disconsolate, thinking only of himself, incapable of recognizing the sorrows of others. Kikuko then pays a visit to Takako, offering flowers as a tribute, announcing she and her husband would be departing by train later that evening to seek a new job in the far regions of Hokkaido. Takako is stunned, to say the least, wordlessly viewing her with open disdain. The scene at the train station is one of the better sequences in the film, as Kikuko holds out hope that Takako will see her off, eagerly looking out the train window, yet what stands out is the serenade of a youthful school choir, establishing a localized sentiment, one with roots in the community, sending off the train with high hopes, accentuating the ideals of youth, likely singing about themes of honor, courage, and integrity, perhaps even valor, all traits associated with exemplary behavior and high ideals, none of which can be attributed to her life, as she watches in vain for any sign that her life matters. Meanwhile, Takako is rooted to her place within her own family, clearly overwhelmed by her sister’s suicide, speaking with her father about giving her marriage another chance, as her daughter deserves having the love of two devoted parents. Fully aware that she’d be leaving her father all alone, openly concerned for his welfare, he puts all that aside, reassuring her that he’d be just fine before kneeling to pray at the altar of his deceased daughter. As he does in so many Ozu films, there is a long, final scene of this stoic, solitary father figure alone on the floor of his finally empty home, calmly staring out in the distance, fully aware of his own solitude, accepting it with a quiet resignation.